Oriental Rug Making: A Family Tradition

In many areas of the United States, the leaves have begun to turn from green to shades of autumn, signaling a return to the fall months. It is a time of change for the American landscape, but one that also brings with it the Thanksgiving holiday, steeped in its traditions of family gatherings, and a shared sense of closeness among friends and neighbors.

In keeping with the tradition, today we’ll be looking at the connections created between family members and communities who have enjoyed a long history of Oriental rug making, and the impact Oriental rugs had on their lives and livelihood.

A Global Rug Making Family

With a history that spans thousands of years, well beyond that of many modern-day art forms, Oriental rug making has no concrete origins to draw from. Yet, the tradition among countless tribes and peoples, scattered across such continents as South America, the Middle East, Asia, and elsewhere, gives credence to the notion that handmade rugs have a history distinctly intertwined with tribal and family trees the world over.

Originally the practice grew from an homage to spiritual practices, or for the creation of functional pieces that kept the tents of these largely nomadic weavers comfortable and clean. But as weavers encountered traders, the tradition began its transition from a local activity, to something that helped sustain the lives of weavers, as well as those who supplied these artists with their materials.

Rug making was, and still is, a specialized practice. Still, the marketability of rugs necessarily increased the number of families that produced rugs, as money from their sale began to flow into, many times, poorer homes and communities.

The Rug Family Business

As time wore on, outside traders became much less important to the weavers of Oriental rugs. With material supply chains already in place, as a consequence of needing to keep production costs down and ensure quality, many families eyed the potential of selling their own wares.

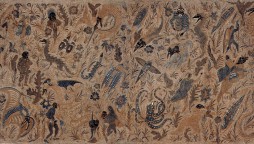

A common scenario ensued, where family shepherds, who had tended their flocks for generations, collected and washed their wool before sending it to other family members in nearby villages. From there, the wool would sometimes be washed again prior to its dyeing process, which involved a thorough stockpiling of both flora and fauna that were used to create the bold color palette of Oriental rugs.

Now having been dried as long, colored strands, the wool yarns would then make their way to weavers, where they would be stretched, interwoven and knotted across wooden frames—many of which had survived several generations of artists.

For months—and in some cases a year or more—these rugs never left their looms, with some of the most delicately crafted pieces needing as many as 1,000 knots-per-square-inch, and in complex patterns that required careful attention and masterful handiwork.

It wasn’t unusual for several generations to make equal contributions in the manufacturing of a rug, where experienced grandparents may draw the rug’s cartoon from which the design was derived; a middle generation of parents who performed the work of putting the rug together; and the children who stood by, watching, as they learned the craft, and when they were old enough, participated as well.

Once completed, the rugs would be rolled and readied for the market, often traveling by way of horseback or by other means through the winding trade pathways that connected to distant lands. Here, they would eventually be sold by family members living in those cities—and improve the way of life for everyone involved.