The Tapestry Rug

THE TAPESTRY RUG - Tapestry is typically a figurative, narrative, art expression.

Tapestry is an ancient form of woven textile art, created for both decorative and functional use. It achieved something of a golden age in medieval and renaissance Europe, where beautifully woven, religiously symbolic tapestries were used in stone and wood structures not only as warm decoration for dark interiors, but as insulation from the unforgiving damp and cold of European winters. While tapestry’s linguistic roots are French (derived from the Old French "tapisserie", meaning "to cover with heavy fabric"), the form’s artistic roots are international. As a tradition, it has existed since at least the 3rd century BC, at which time it was a central art form of Hellenistic Greece, and in the centuries that followed it slowly evolved to its apex in northern Europe, where tapestries became the most significant expressive art of the both the monarchy and the church.

Though tapestry developed independently and uniquely in civilizations throughout the world, it has always retained the standard construction that defines the form. Hand-woven on vertical, or somewhat less commonly, floor looms, tapestries are made by passing weft threads through a tightly suspended warp. There is no pile in tapestry, but instead, the weft itself is used to create the design. This technique is known as weft-faced weaving, distinct from piled weaving, in which both warp and weft are usually hidden.

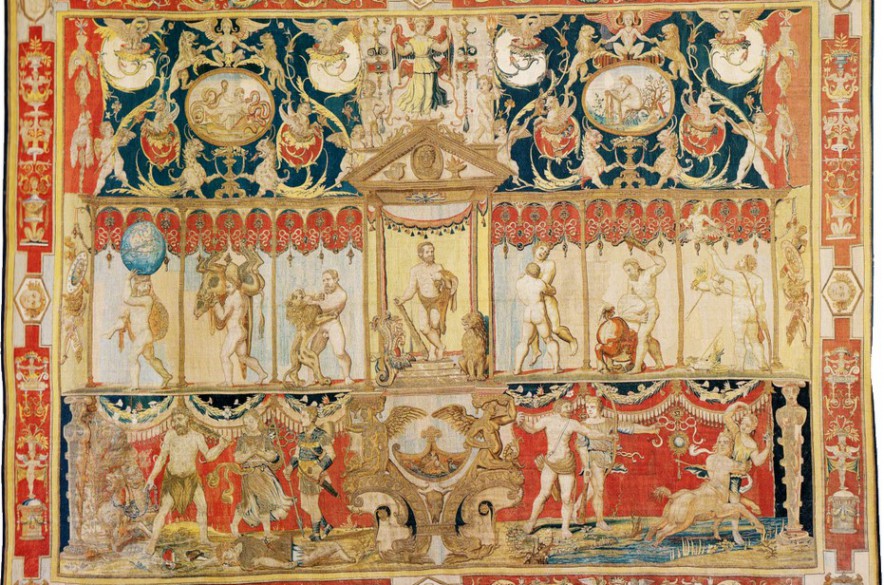

Tapestry is typically a figurative, even narrative, art. Eschewing the decorative for the pictorial, weavers create scenes depicting humans, animals, and nature engaged in meaningful and symbolic interaction. The stories tapestries depict are often religiously and morally instructive, and in the finest examples express a true urgency of communication in the weaver’s hand.

The functional quality of tapestries can be truly surprising. Woven with thick, heavy strands of cotton and wool, the wall hangings of medieval Europe effectively and efficiently protected rooms from the unforgiving damp and cold of winter, and while their original functional quality is of less value today, its history helps to explain the typically enormous size of early examples of the form. Many tapestries were originally woven to cover entire palatial walls of churches and castles, and their creation was an enormously time consuming and labor-heavy undertaking. As the form evolved, immense centralized workshops arose in commercial centers throughout Europe, where the enormous looms, weavers, and importantly, capital investment could be efficiently organized.

Over time, as the art form evolved, the most common narrative scenes of tapestries took on archetypal significance, and what we can now refer to as standard motifs arose: the hunt, the four seasons, the continuous cycles of birth and death. By the 16th centuries, these magnificently detailed, expertly rendered motifs, assembled by hundreds of hands working for thousands of hours, had in the most exemplary tapestries developed enormously complex layers of detail and received meaning.

The form continues to thrive in cultures throughout the world. Persian, Turkish, and European tapestries of the 14th through the 19th centuries are among the most highly-valued antiques on the textile market. They are true relics of the human voice, quiet reflections of the concerns, the fears, and the beliefs of their creators. They may very well be the most explicitly expressive form of woven art we have.